February 18, 2026

Belonging as Campus Infrastructure

Why Belonging Matters Now

Higher education is navigating a period of profound recalibration. Enrollment pressures, demographic shifts, mental health concerns, and questions of relevance are converging at once. In this environment, student connection is no longer a “nice to have” or a student life initiative. However, through our research and experience with campus projects, we’ve learned that foundational infrastructure can contribute greatly to a sense of belonging.

When students feel like they don’t fit, they leave. When they struggle to find their place, they disengage. Campus environments often send signals, intentional or not, that certain people don’t belong, failing the students they claim to serve.

At Progressive Companies, we design campus environments that allow students to let down their defenses, feel seen, supported, and connected to a larger purpose. The condition of belonging is built into the physical environment; deepening student engagement and allowing campuses to function as true academic communities.

Moving Beyond Space to Experience

Too often, belonging is discussed as a program or a policy. We define and approach it as an experience, shaped by the built environment over time.

Students experience belonging when they can:

- Recognize themselves in a space– through cultural representation and design that reflects diverse lived experiences

- Participate without instruction – through intuitive wayfinding and environmental cues that replace signage

- Find agency and comfort – through flexible, multipurpose spaces that support both connection and refuge

- Move between modes of being – from academic to social to personal, without friction or self-consciousness

Architecture does not create belonging on its own. But it can remove friction, amplify connection, and signal permission. When done well, the campus becomes legible. Students don’t ask, “Am I allowed here?” They already know.

A Nuanced, Performance-Based View

We measure success through outcomes that institutions already value:

- Retention and student persistence: Do students return? Do students ask for help before they’re in crisis? Spaces that support informal connection and routine presence in a safe environment help to reduce anxiety, support different learning styles, and encourages help-seeking.

- Utilization patterns: Are spaces being used as intended? Consistent, purposeful use signals that a space is working as anticipated.

- Campus identity: Do students feel the institution’s values in their daily life? Places should express what a campus stands for through experience, not signage.

- Equity of experience: Do commuter students, first-generation students, and under-resourced students navigate campus as confidently as their peers? Inclusive design ensures social capital isn’t a prerequisite for belonging.

When campuses are intentional in design, belonging becomes reinforcement of the network of moments, scaled from the individual seat to the campus system.

Infrastructure Signals That Shape Behavior

People read buildings instinctively. Materiality, light, sound, adjacencies, and thresholds all send cues about how to behave and who is welcome.

For example, a museum gallery and an Apple Store may share wood floors, white walls, and curated displays, yet one invites quiet contemplation while the other welcomes conversation and energy. The difference is not material; it is permission communicated through spatial design.

A vibrant learning commons and a quiet reading room may share similar finishes, yet communicate entirely different permissions. Successful campuses are intentional about these signals, creating gradients of energy rather than binary zones.

Belonging in Practice: Designing for the Whole Campus Population

Belonging in practice serves the full reality of today’s campus: from commuter students navigating long gaps between their classes, to neurodiverse learners seeking both stimulation and refuge, to community members engaging with public-facing facilities. Designing for belonging means anticipating overlap, managing tension, and creating dignity for all users without compromising comfort or safety.

In the next three sections, we’ll explore designing for belonging through three different lenses: Student housing, learning environments, and campus architecture.

Student Housing: The Space Where Identity Forms

Most campus housing design is often pushed to the edge of the pro forma. Bedrooms are kept to the minimum: a bed, a desk, a wardrobe, and a door that swings. In these environments, the only place to sit and connect is frequently the bed itself.

That matters.

Our work in student housing is informed by research, such as Sexual Citizens: Sex, Power, and Assault on Campus by Jennifer Hirsch and Shamus Khan, which highlights that students are actively forming identity, negotiating power, and learning consent during their college years. Housing serves as more than a space where students sleep. It’s where they practice being adults with others.

Yet current design removes the spatial conditions that support choice, clarity, and safety. When a space offers no alternative postures for conversation, presence, or pause, it can unintentionally collapse nuance and agency.

Our approach provides options, prioritizing dignity over density. We design housing environments that provide light, a lounge, and options for interaction, spaces to gather without escalation, and to retreat without isolation. These simple strategies are essential infrastructure for young adults learning to navigate their identity and relationships.

Students need environments that support the full range of human interaction, rather than being prescribed by inherited standards rooted in narrow cultural assumptions.

Learning Environments: Designing the Signals Students Read

At a current Learning Resource Center, we invited our clients to step out of their professional roles and into the lived realities of students. Through a structured “day in the life” exercise, participants navigated the building as:

- A first-generation Black woman arriving to research and write a paper

- A student using a wheelchair with significant mobility limitations

- Students arriving alone, in groups, between classes, or late in the day

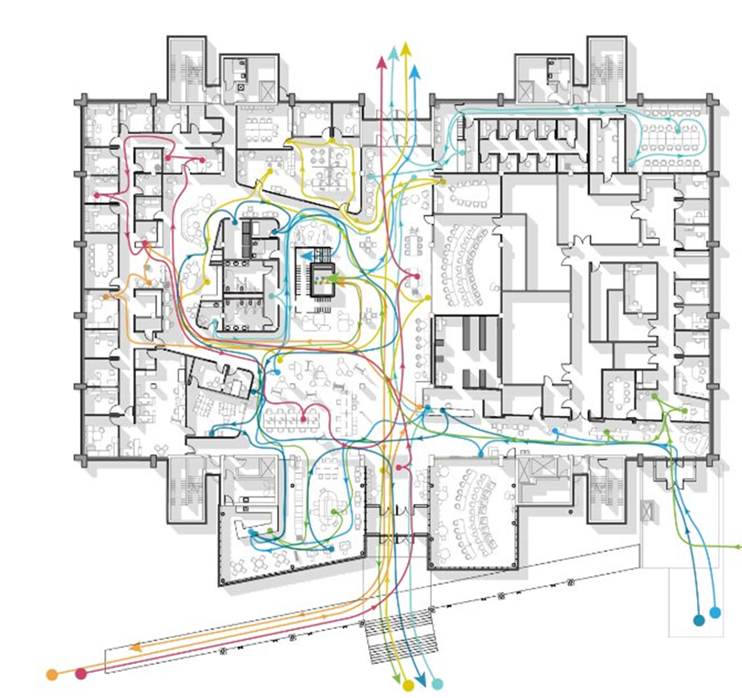

We mapped moments of uncertainty, confidence, overlap, and connection. Where paths crossed, where identities intersected, and where students needed reassurance.

These findings became our design priorities.

Key moments such as entries, direction kiosks, and reception points were designed as places of welcome and orientation, not control.

Rather than relying on signage to dictate behavior, we let architecture send the signals. Students intuitively read space through light, sound, materiality, ceiling height, and furniture posture.

The task wasn’t to “design for everyone”, but to design from lived experience, addressing real needs and then empowering the daily operations of the space to carry this ethic forward.

We designed gradients of activity rather than binary zones, trusting students to curate how spaces are used.

Campus Architecture: What Buildings Say About Belonging

Campus buildings must do more than meet programmatic needs. They set the tone for future development, express institutional values, and signal who belongs.

Many traditional campuses are grounded in Georgian or Jeffersonian architectural language, powerful symbols of history and identity for some, yet potentially intimidating or alienating for others. The architectural language of a campus tells prospective and current students who this place is built for.

For first-generation and low-income students, the grandeur of classical architecture can reinforce feelings of distance from an academic culture that feels inherited rather than inviting. For students from diverse cultural backgrounds, Western colonial forms may not reflect their own identities or histories.

Belonging requires architecture that reflects its time and place while engaging respectfully with context.

Our work focuses on:

- Respecting scale and proportion to maintain continuity

- Using complementary materials in contemporary ways

- Reinterpreting traditional details without mimicry

- Creating exterior transition spaces such as courtyards and gardens

- Emphasizing longevity, sustainability, and human interaction

- Using landscape as a unifying element

New architecture becomes part of an ongoing dialogue, evolving the language in ways that expand rather than restrict who feels welcome.

Progressive Companies: Transforming Campuses. Empowering People.

College has long served as a place of growth and exploration for students; in knowledge, finding their identities, navigating social dynamics, and learning life skills. By creating a sense of belonging along with intentional spaces on campus for these different needs, universities can increase retention and foster an environment that supports the long-term goals of the institution.

Belonging is a design concept that we bring to planning, renovation, and new construction. It is embedded early, shaping how we listen, test, and design across housing, learning environments, and the connective tissue of campus.

Our team designs for choice, overlap, and agency, prioritizing comfort without surveillance, clarity without instruction, and identity without exclusion.

If you want to explore what this might look like on your campus, reach out to our team to start the conversation. A Strategic Residential Plan may be a great place to start, together.